CCC Service in Segregation

Junior company 303-C of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was Incorporated at Fort Hoyle, Maryland, in 1933 as one of the original six segregated black companies in PA to compensate for the over 1700 black recruits in Pennsylvania’s CCC. The company, existing from May 1933 to at least March 1942, spent most of its posting in Benezette, PA, at camp S-84, located in Elk County. On November 15, 1941, the company, numbering 90 men, was transferred from Phillipsburg S-119 to the Clearfield [Tree] Nursery known in what is Simon B. Elliott State Park. The camp known as S-116, situated eight miles north of Clearfield, established on May 30th, 1933, had previously been occupied by a white junior CCC company. Despite the high level of white men leaving their CCC companies as the depression era ended and preparations for war increased, the need for labor in ongoing CCC projects continued. Being kept intact, Co 303-C did not experience the loss of men suffered by white junior companies at that time.

Building Roots

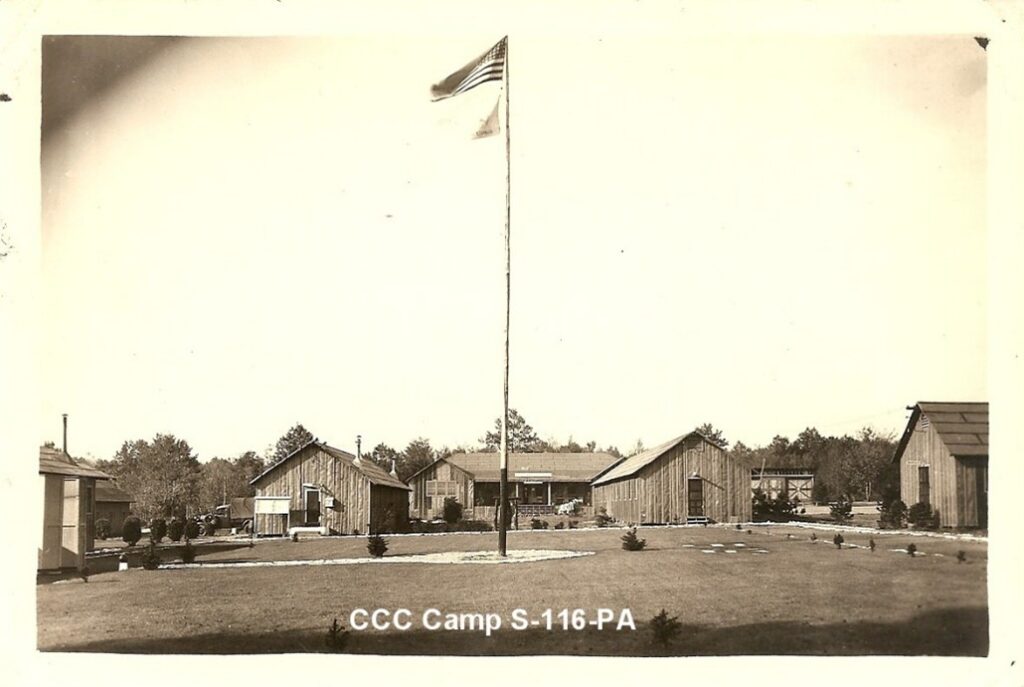

“During 1933, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) established Camp S-116 on land along the edge of the nursery and built the cabins, pavilions, roads, trails, and many other buildings that exist today in the park.”- Simon B. Elliott State Park Website, DCNR.

Projects that Co 303-C worked on at the Clearfield Camp centered around the tree nursery operations of collecting conifer cones and hardwood seedlings, “lifting, counting, packing and shipping seedlings and transplants, making beds and seeding, transplanting, weeding and general maintenance.” The field planting of seedlings and transplants occurred in the spring and fall. During the summer and winter, the men of 303-C constructed and maintained truck trails and bridges. Being at S-116 for under six months, Co 303-C may not have worked in all these manners.

Nourishment and Recreation: Daily Life and Community Engagement

All the men were provided with breakfast, dinner, and supper. Food items such as meats, potatoes, eggs, bread, milk, cheese, and onions were ordered through approved contracts, while fish, fruit, and vegetables were bought in local open markets. Mess or kitchen expenses were tracked meticulously with pre-approved menus, including food and labor costs. Company 303-C’s kitchen had to justify budgetary deficits in November 1941 when no subsistence order was received until after moving from Phillipsburg, causing the need to purchase goods from nearby camps. The expense of surplus kitchen staff for five days that month also required explanation.

Camp S 116 from www.GoDubois.com

As of December 1941, outdoor recreational activities that Co 303-C participated in included boxing, hard and softball, open-air basketball, volleyball, badminton, and horseshoe. The company formed a league that played hardball against nearby camps and local teams. Though boxing was mainly confined to the camp, some men of 303-C competed locally in boxing matches. When men in the camp interacted with the community through recreational activities, it was considered an act of goodwill. An indoor recreation hall at the Clearfield camp included pool tables, ping pong, a record player, a piano, and a weekly movie showing for the company. Men would visit the town of Clearfield for a recreational trip every Saturday. Religious services were held weekly by visiting local colored ministers. A protestant chaplain commissioned by the CCC visited the camp three times a month to discuss camp and social living with the men.

Operational Excellence with Limited Resources

According to the December 4, 1941 camp inspection report by Patrick J. King, the men of Co 303-C were excellently dressed and followed safety regulations. Upon the closing of camp S-116 on March 13, 1942, items were examined, inventoried, and loaded for transport to Co 303-C’s new posting at Fleetwood Depot. The care given to closing camp S-116 differed from reports of other PA CCC camps where the wasteful destruction or disposal of valuable resources occurred, including blankets, utensils, food, and even abandoned trucks. Camp Commander McNeil of camp S-116 defended the allegations by inviting the public to witness the departure process. He highlighted his financial liability as camp commander for appropriately utilizing and maintaining camp resources.

On-hand supplies at camp S-116 were limited. Blankets and sheets were well stocked on the shelves, but not clothing, underwear, stockings, shoes, gloves, and toilet kits. These supplies required a requisition to the Fleetwood, PA depot, where supplies were maintained. Camp Inspector Patrick J. King commented on how the lack of stocked supplies affected men’s productivity. “If a boy loses his gloves there are no other to give him until a new pair comes from Fleetwood.”

The wells at S-116 provided ample clean water in both winter and summer.

The camp was well maintained by Co 303-C. The kitchen, scullery, refrigerator, subsistence storeroom, infirmary, wash and shower rooms, and barracks were all in “good order.” As of December 1941, the recreation hall was functional, even if not as attractive as recreation halls found at other CCC camps. The Education building was “a superior type.” Pit-type latrines adjoined the building. Camp S-116 had a spacious reading room with over 1000 books and various newspapers and magazines.

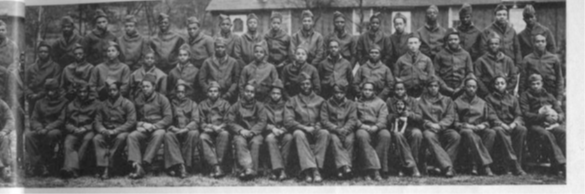

Part 1: Co 303 C at S 84 Benezette, PA 1936 / Photo Courtesy of DCNR PA CCC Online Archive

Learning Life and Technical Skills

Along with their work enhancing PA State forests at Clearfield Nursery, the men of Co 303-C gained technical and educational training four nights a week. All the company 303-C men were trained in American Red Cross First Aid, health & hygiene, occupational information, job finding, and safety for administrative training. Some men qualified as First Aid instructors.

Technical staff led safety meetings twice monthly. The men also received formal training to be instructors and leaders. Academic courses provided included reading and arithmetic. Vocational training included photography, woodshop, and typing. When asked in December 1941, many Co 303-C men found immense value in the education and training at the CCC camps.

The Winding Down of the CCC era

Lt Andrew G. Gorski, 303-C company commander from November 1939, was called to active duty in January 1942. Upon Gorski’s leave, Lt John H. McNeil, USNR, Subaltern since November 1941, took command of 303-C at s-116.

On March 6, 1942, an additional 70 African American men were shipped to Clearfield Nursery after a camp closure in Austin, PA. The company included technical personnel, all colored, project superintendent Theodore H. Smith, George H. Hines, and Emmanuel Davis as foremen, and Lewis Ulen, a mechanic. Other specialists of note served in 303-C at S-116-PA. S R Crocco, an engineer, and C.B. Plessinger, a Forester, were previously of company 321-C.

Part 2: Co 303 C at S 84 Benezette, PA 1936 / Photo Courtesy of DCNR PA CCC Online Archive

Unequal Yet Essential: Legacy and Struggles

The struggles and inequalities faced by the black CCC companies, such as Co 303-C, are integral parts of our history that deserve recognition. Despite their vital contributions to infrastructure development in Pennsylvania’s State Forests and Parks during the 1930s and early 1940s, these companies were often subjected to discriminatory practices within the CCC. George Crump’s account in the Philadelphia Tribune from July 1933 sheds light on the disparities experienced firsthand by Co 303-C, from receiving used and stained clothing while their white counterparts enjoyed crisp new uniforms to being relegated to odorous stables while white companies were provided better accommodations. Crump’s poignant statement, “We were all treated alike, except in privileges, the white boys received first choice in everything,” underscores the systemic inequalities that persisted within the CCC despite its purported mission of equal treatment. By sharing these untold stories, we honor black CCC companies’ contributions and confront our past’s uncomfortable truths, fostering a more inclusive understanding of our history.

Documentation and records of 303-C at Clearfield Nursery are sparse. Still, sources such as DCNR’s CCC Online Archive, an inspection report from the National Archives, periodicals of the time, and the book At Work in Penn’s Woods by Joseph M. Speakman were helpful. The knowledge and assistance provided by PA DCNR, Department of Forestry staff, and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission allowed for the telling of this story.

Written by Martha Moon, PPFF and PA Conservation Heritage Project Intern

If you or someone you know has untold conservation stories to highlight, please email [email protected]

Other Resources:

- Joseph M. Speakman, At Work in Penn’s Woods: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Pennsylvania (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006)

- History of Simon B. Elliott State Park

- Archaeology and the Segregated CCC: Giving Voice to the Voiceless

- Accomplishments of African Americans in the CCC (1933-1942): Selected Examples | Living New Deal