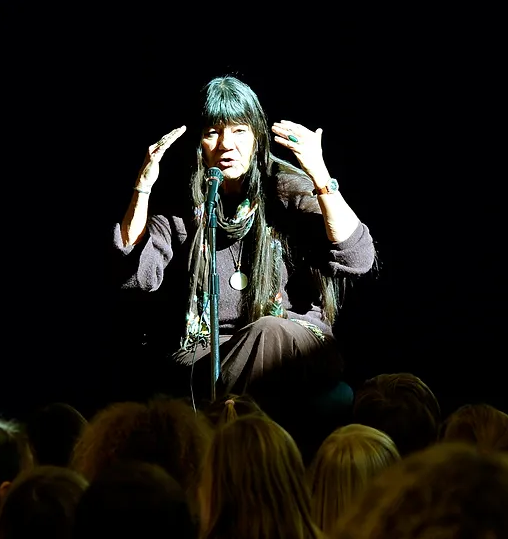

Known as an indigenous storyteller for over four decades, Dovie Thomason (Lakota and Kiowa Apache) resides in Harrisburg, PA., traveling frequently, especially along the eastern seaboard. Born in Chicago, Dovie moved to Texas, living with her dad and grandparents, where storytelling was a part of everyday family life. Considered Dovie’s greatest inspiration, her grandmother intertwined storytelling with day-to-day tasks such as shelling beans. To Dovie, these interactions took visiting with family to the next level.

Dovie’s grandmother, born in the 1890s, retained great knowledge of indigenous stories and traditions even as she witnessed so much change over her lifetime. It wasn’t until later in life that Dovie realized how her grandmother’s storytelling carried on native customs.

Dovie sees her experience of moving from Chicago to Texas and back as moving between the Northern and Southern Plains.

Bridging Cultures Through Storytelling: From Classroom to Community

Dovie studied literature in college and soon recognized Indigenous storytelling as a form of classic literature. Many indigenous storytellers continue to be older, making preserving their culturally based stories a vital effort.

Having moved to Cleveland, Ohio for graduate school, Dovie began teaching high school students from many different cultural backgrounds. Many students at the school struggled academically coming from homes where English was their second language. Dovie utilized her storytelling to connect students with the material they were studying, connecting Indigenous stories to those of the students’ own cultures. She discovered that by using storytelling as a teaching technique, the students in her classes were more engaged and their understanding of the curriculum subjects greatly improved. As she became known for her teaching technique, Dovie was invited to visit other classrooms, and her career as a storyteller and educator blossomed.

After finishing graduate school, Dovie moved around the eastern seaboard. She first lived in New England, then moved to Virginia, Maryland, and finally Pennsylvania. Dovie became acquainted with Jimmy Little Turtle, an Indigenous American leader in Harrisburg. Undoubtedly an activist for indigenous culture, Jimmy Little Turtle was also the business owner of Jimmy Little Turtle’s Indian Arts & Crafts in New Cumberland, PA. He and his mother Viola White Water, of Shawnee heritage, were committed to keeping native history alive.

In 1977, Jimmy created the Viola White Water Foundation to continue the legacy of “promoting Indian culture and education,” continuing his mother’s tireless work. Viola and Jimmy diligently got Pennsylvania’s State Historical Society to recognize their Indigenous voices and stories. When living in Virginia, Dovie spent much of her time visiting Jimmy Little Turtle. When Jimmy decided to retire to Florida, Dovie purchased his home, officially moving to Harrisburg.

The Viola Whitewater Foundation sadly dissolved in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through the work of Jimmy Little Turtle and then Dovie, the Foundation was able to shine a light on Indigenous cultural history. Dovie took a special interest in making the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, PA, publicly known for its cultural significance to Indigenous groups across the United States, utilizing the foundation’s resources to support the endeavor financially. In 2003, the Viola White Water Foundation sponsored a historical marker placed at the school’s cemetery, which now lies on the Carlisle Army Barracks property. The Viola White Water Foundation’s reach extends beyond central Pennsylvania though, funding projects such as the Akwesasne Freedom School in Northern New York State in the early 1980s.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, founded in 1879 and closed in 1918, was a model for hundreds of other Indian schools in the United States “to remove Indigenous children from the families and communities to assimilate them and stop the passing-on of Indigenous culture.” Finding herself deeply connected to uncovering the school’s history, Dovie researched how the Harrisburg industry and agriculture utilized students for labor. The utilization, and potential for exploitation, of the students’ labor wove them into regional history. Through efforts such as Dovie’s, the Carlisle Indian School has garnered more and more attention in the media and published literature, including the book, Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, and Reclamations, in which she is a contributing author.

“Some stories are too painful to be told…. Some stories must be told.” – Dovie Thomason, (Carlisle Indian School Symposium, Oct. 5-6, 2012, Carlisle Indian Industrial School:

Indigenous Histories, Memories, and Reclamations, p. 21.)

Photo credit: The Burg

Redefining Conservation: Traditional Stories to Modern Environmental Advocacy

For the first twenty years of her career, Dovie only told stories within her indigenous tradition but then expanded her stories and programs to address the greater issues of this modern era. Dovie believes that looking through the lens of an Indigenous person and their participation in the surrounding area can change other people’s perspectives.

According to Dovie, the Indigenous perspective that humans are in a relationship with all living things creates a greater dignity and respect for all things that are not human. Dovie describes the language of conservation as “interesting.” To truly conserve is to restore balance between living things. Storytelling helps to show that our place in the world is to find balance.

Dovie believes people are not stewards of the forest, but instead share a co-dependence with the forest. Trees have just as much of a right to live as people. After World War II, the ideology of “better living through chemistry” introduced many chemicals, harmful to people and the forest. This use of chemicals inspired the book Silent Spring (1962) by Pennsylvania native Rachel Carson. Many states are now recalibrating and revitalizing initiatives to cultivate the vitality of forests and natural resources.

Lessons from the Skies: Reflections on Birds and Environmental Regeneration

Dovie describes herself as a “bird person.” She looks at wild birds as a good model for balanced human behavior. For example, blue jays plant more arboreal forests than humans, carrying four to five acorns at a time and burying the acorns to grow forests. Eleven species of oak trees depend on jays to propagate. Dovie asks how people can carry forests forward as the blue jays do. Another bird of note for Dovie is the thrush which carries seeds for berries, which when grown are a source of food for deer, allowing trees and their seedlings to grow unharmed.

Along with her admiration for birds, Dovie holds Rachel Carson in high regard and credits Carson with inciting the creation of the EPA and the continuation of robin populations, considered “early to spring,” increasing the bird species’ risk of being harmed by pesticides. In her latest story, Dovie pays homage to the efforts of Rachel Carson and bird populations in the proliferation of natural resources and the environment.

Dovie with a bluejay

Embracing Perspectives: A Vision of Diversity, Collaboration, and the Preservation of Indigenous Stories

Diversity to Dovie is not only about race, ethnicity, or age but also about embodying one’s perspective. She works collaboratively with others to spread stories, actively looking for people to share stories and create relationships. Determining what is important to talk about is an important aspect of storytelling. It is the nature of the human species to be collaborative; few people can argue with highlighting things that matter to all of us.

To Dovie, storytelling has been a continuous tradition. Hearing talk of the preservation of storytelling, Dovie initially questioned what aspect of the tradition needed to be restored. Through her work with the Carlisle Indian School, Dovie discovered that so much indigenous American culture was lost.

Storytelling Beyond Folklore: A Tool for Training, Rehabilitation, and Scientific Narratives

Dovie has worked with people of many different backgrounds. Storytelling surpasses the mold of folklore and cultural history, being utilized in training for occupations such as first responders and among prison inmates to cultivate rehabilitation through stories of decisions and the consequences. Collaborating with scientists, Dovie finds comradery in being interested in answering the “why,” including the causes and effects of many of today’s issues. Dovie encourages scientific end narratives to bring out what values matter to people and weave those values into a story that further encourages collaboration.

A Legacy of Impactful Storytelling and Cultural Advocacy

One of the proudest moments of Dovie’s storytelling career was the day before the National Museum of the American Indian opened in Washington D.C. She was invited to give a storytelling event in the new building before it opened to the public. The audience of construction workers, architects, maintenance staff, volunteers, etc., had committed months, if not years to creating space to house Indigenous American histories, cultures, and stories. The event was an extraordinary evening for people from many communities. Dovie was honored to be there to thank them for their support and hard work.

Another special event that stands out to Dovie is a 2009 TEDx talk in Pittsburgh. She was their first “Native” voice. Dovie also takes pride in having represented the U.S. at a “literary festival” as the only spoken word artist, cementing her opinion of storytelling as a formidable form of literature, describing these experiences as “humbling and wonderful to have brought storytelling into view for so many—generations, even!!”

Dovie’s commitment to including the next generation in impactful topics includes inspiring a revitalization of efforts to find balance with nature and preserve it for those that come after. Her devotion to her craft makes her an irreplaceable asset to not only conservation in Pennsylvania but collaboration on a global scale, focusing on “things that matter.”

Environmental Awareness: Forests Matter!

Dovie believes there is something for everyone in parks and forests, yet we often take these places for granted. The spread of information about forests and natural resources does not reach everyone. Until recently, Dovie did not know about the “Serpentine Barrens” of Goat Hill in Pennsylvania’s William Penn Forest. She believed the only barrens that existed were in Ireland.

Dovie’s storytelling and initiatives like the Pennsylvania Conservation Heritage Project create a gateway to consciousness and awareness of treasured environmental resources. Will you step through?

If you have stories of diversity and inclusion in environmental conservation or want us to highlight a certain conservationist or naturalist in Pennsylvania with unique perspectives, email [email protected]

Additional Resources:

- Bentley, Matthew, and John D. Bloom. The Imperial Gridiron: Manhood, Civilization, and Football at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2022.

- Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center

- Dovie Thomason: Her website

- Fear-Segal, Jacqueline, and Susan D. Rose, eds. Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, and Reclamations. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

- Her Garden Grows: Dovie Thomason uses oral narrative to recover Indigenous lives, histories – TheBurg

- NPS article: The Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Assimilation with Education after the Indian Wars (Teaching with Historic Places).

- White, Louellyn. Free To Be Mohawk: Indigenous Education at the Akwesasne Freedom School. Vol. 12. New Directions in Native American Studies. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015.

- Rachel Carson: Documentary

- Press Release, Fact Sheet, and Educator’s Guide

- Rachel Carson Homestead

- Thomason, Dovie. “The Spirit Survives.” In Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, and Reclamations, edited by Jacqueline Fear-Segal and Susan D. Rose, 315–332. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016.

Written by Martha Moon, PPFF Conservation Heritage Project Intern

Photos Provided by Dovie Thomason