Location

Within the Moshannon and Elk State Forests in Central Pennsylvania lies one of the state’s 18 official state forest hiking trails: The Quehanna Trail. The Quehanna Trail is a 73.2 mile loop that passes through Pennsylvania’s largest wild area, the Quehanna Wild Area. The trail meanders through three counties: Clearfield, Cameron, and Elk, as well as State Game Lands #94 and #34.

Route

Traditionally, the QT begins at Parker Dam State Park, with hikers walking the loop counterclockwise. However, there are nine other official trailheads at the above state forest parking lots, promoting flexibility in navigating the trail. Offering the greatest flexibility are the three cross-connector trails within the main 73.2 mile loop of the QT: the Cutoff Trail, the West Cross Connector Trail, and the East Cross Connector Trail. The 1.7 mile long Cutoff Trail is the first cross-connector trail, the junction at 3.5 miles of the QT. The second is the 6.3 mile West Cross Connector Trail, its junction with the QT at 5.0 miles. Last but not least, 9.4 East Cross Connector Trail joins the QT at 20.3 miles. These cross connectors are one of the main reasons retired forester, Bob Merrill, considers the Quehanna Trail a “premier hiking trail in PA.” The cross connectors create options for a shorter day hike as opposed to the commitment of a days-long trail. The QT is mostly well blazed with frequent orange blazes.

The Sights

About 34 miles of the QT, and most of the East Cross Connector Trail, passes through the Quehanna Wild Area, the largest Wild Area in PA. A State Forest Wild Area is protected to preserve the “wild character” of an area, and this “wild character” is the main attraction of the QT. The trail is in one of the most remote places in PA. For example, there are no permanent residents for about 21 miles along the Quehanna Highway between Medix Run and Karthaus.

@OneEyeWanderz spends time backpacking the Quehanna Trail taking on the views.

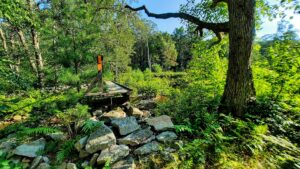

The remote nature of the Quehanna Wild Area alone could satisfy hikers’ desire for “wild character,” but the aesthetic is accentuated by the unique ecosystems along the trail. The Quehanna Trail passes through open meadows, high plateau, hemlock swamp, valleys, and vistas. The great diversity of ecosystems of course means a great diversity of plants. Retired forester and devoted volunteer Ralph Harrison once wrote that, “It seems I find a new plant or shrub on every trip to the Wild Area.”

The wildlife is just as varied as the ecosystems they inhabit along the Quehanna Trail. Animal sightings from hikes are fondly remembered by all who hike the trail. Author Tom Thwaites wrote that, “The largest bear I have ever seen outside a zoo was on the Quehanna.” Harrison confidently claims that, “In most places deer, black bear, bobcats, rattlesnakes, and even elk, outnumber people.” The elk are an especially popular draw. KTA volunteer, Paul Shaw, had a remarkable encounter when he stumbled upon a group of six elk, and the herd walked parallel with him as he continued on the Quehanna Trail for several minutes! Another KTA volunteer, Ginny Musser, makes a point to visit Parker Dam State Park every year to “Frolic with the elk.”

How remarkable is it that we have such a wonderful trail in the heart of Pennsylvania? It’s easy to forget that the trails we have today were not always here, and in fact there were times when they came close to disappearing forever. The history of the land through which the Quehanna Trail travels is wrought with violence, ecological devastation, nuclear experimentation, and a tornado. At the same time, the land has been nurtured by countless individuals, from the indigenous peoples of the region, to kind-hearted state employees, to professors, to prisoners, and dozens, perhaps hundreds, of volunteers. The Quehanna Trail is not a miracle, but the culmination of dedication from so many. Walk with me now, if not along the trail itself, then through the story it has to tell.

Before the Quehanna Trail

Before 1810: Pre-Colonial

The Quehanna Wild Area and surrounding regions was a territory claimed by the Seneca Nation. Indigenous people were mostly settled in semi-permanent villages near rivers and stream bottoms. One such village was Chincleclamousche, which occupied almost all of modern day Moshannon and Elk State Forests. They would set fires to the forest to promote the growth of blueberries and create brushy areas to attract game species, and supplemented their diets with farmed crops including maize and squash.

After the Revolutionary War, colonists began migrating to Chincleclamousche Township, and in 1791, one of the last battles between colonists and indigenous peoples was fought near the village of Sinnemahoning. Clearfield County was established from the former Chincleclamousche lands in 1804, and by 1810, the first permanent white settlers arrived, settling along Sinnemahoning Creek.

1810-1965: Land Development

Hunting

Hunters and furtrappers ventured into the Quehanna Wild Area, building cabins for their families. These hunting camps spread throughout the state, as did a “spiderweb of trails” from the primitive roads they carved from the forest.

Overhunting extirpated many local mammals, including eastern woodland bison, eastern elk, and more. The last panther in the region was likely killed in 1891, with the last grey wolf following suit the next year. The Pennsylvania Game Commission has since re-introduced many of these species, like the elk in 1913. The eastern coyote occupied the niche left by the extirpated grey wolf.

With all of the fond accounts of hikers encountering elk along the Quehanna Trail, it’s crazy to think how, for a time, there were no elk in the region at all. Despite colonial development and hunting driving animals out of the area, the diversity of life present along the Quehanna Trail today still inspires hikers to tell vivid stories of their wildlife encounters.

Logging

In 1820, timber became an export good for non-local markets. People would use nearby rivers to transport logs. To speed up the process, loggers designed splash dams, temporary structures built out of earth with a central wooden gate. An artificial lake would form behind the closed gate, atop which loggers would place their harvest. When the gate was opened, the water would rush downstream, carrying the logs with it.

In 1870, a splash dam was built at the junction of Mosquito Creek, Gifford Run, and Twelve Mile Run. While most splash dams were relatively small, Corporation Dam, was an exception; at a couple hundred yards long and at least ten feet tall, Corporation Dam gathered the three streams into a massive artificial lake that was likely half a mile long and up to a quarter of a mile across. Sediments from the loosened soils of the deforested area settled in the lake, forming a layer of mud at least eight feet deep. Soft and unstable, the three streams were able to carve through the earth with ease, resulting in steep, unstable slopes, and deep, swift currents.

Photo by @OneEyeWanderz along the Quehanna Trail

The first commercial logging phase in the Moshannon State Forest targeted old growth white pine. The most valuable white pines were called spars, towering trees at least 93 feet long and 18 inches in diameter. Most white pine was used for lumber, but spars were destined to become the ship masts, sailing across the Atlantic for trade with England. The mighty spars were the first trees to disappear from the Moshannon. The second most valuable tree at the time was hemlock, its bark full of tannic acid. At a time when horses were a primary means of travel and machines ran with leather belts instead of gears, it’s no wonder how the value of the hemlock’s bark got to be so high.

In 1890, the rate of deforestation increased dramatically with the advent of railroad logging. Previously, logging was restricted to areas near rivers, but with railroads, companies could clearcut almost anywhere. Species began disappearing. The last old growth hemlock stands in the Wild Area were harvested in 1908.and by 1915 nearly everything was clearcut. As if to mock modern-day environmentalists, it was apparently common for the directors of logging companies “to once a year ride the rails around their domain, to assure themselves of the totality of cut.”

In a healthy forest, tree bark is thick and soil is damp, making it difficult for fires to catch and spread. Without trees, brushy plants grew quickly in the vacant lands, easily catching fire. Many areas were intentionally set ablaze with the hopes of replacing the shrubs and trees of no market value with arable land. Ironically, these fires would kill off any remaining white pine/hemlock seeds/saplings. Railroad logging exacerbated the fire issues, as sparks from the tracks would ignite the tindered fields. There is speculation that fires destroyed even more of the forest than logging.

What the fires didn’t kill was oak, which is resistant to the flames. The oaks grew to co-dominate the regenerated forest, along with fast-growing maple. Atop the Quehanna plateau, it wasn’t fire preventing the white pines and hemlocks from returning, but water. Hemlock trees transpire a lot, keeping the water table relatively low. When the helmlocks were all logged, the water table rose, resulting in ecological succession favoring ferns and brackens, explaining the frequent meadow ecosystems along the QT uncommon elsewhere in PA.

Not only is the logging history of the region the origin of many of the ecosystems prized along the Quehanna Trail today, but the scars left on the land make up many of the trails used to enjoy the scenery. Old logging roads, railroad grades, and pipelines are the trails now blazed orange as a part of this state forest hiking trail.

Photo Credit @OneEyeWanderz

Curtis-Wright Corporation

Following WWII, the US Department of Defense signed a contract with the Curtis-Wright Corporation to have them develop a nuclear powered jet engine. Curtis-Wright purchased a 16-sided polygon of about 80 square miles from the secluded Quehanna region. In order to keep the research a secret, hunting in the area was prohibited to discourage stray persons from stumbling across classified intelligence.

The dream of developing nuclear powered jet engines required infrastructure to get going, so in came the Quehanna Highway, a nuclear reactor, and manufacturing/nuclear/industrial facilities. Concrete test bunkers with steel doors and grids of thick glass were constructed. From within, an observer could safely watch a demonstration of a jet engine bolted to a slab of concrete. Unfortunately for the Curtis-Wright Corporation, the operation failed (nuclear-powered jet engines still do not exist, after all), and by 1960 portions of the polygon were sold back to the Department of Forestry.

Because no hunting was allowed in the region, the deer population exploded. The herds ate almost everything, including the seeds of oaks and maples. Meanwhile, in the late 60s-early 70s, the oak leaf roller was destroying the population of mature oak trees, similar to the gypsy moth. With the mature trees dying and the seeds being eaten, the forests became stunted; forester John Sidelinger remembers how, 50 years ago, he would be driving down the Quehanna Highway for grad school, and he could see over the canopy because it was so short. Even the deer were stunted. There were too many deer for a healthy forest to support, and with fewer acorns for winter foraging, the deer were starving. Sidelinger surveyed the deer population in the area as part of his grad program back in the early 70s. The average adult male weighed only 80 pounds, compared to the 130 pounds common today.

The Department of Forestry finally reacquired most of the Curtis Wright lands in 1965, and the region was declared the first wilderness area, the Quehanna Wilderness Area. State Forests Monuments and Natural Areas were renamed as Wild Areas, starting with the Quehanna Wild Area in December 1970.

Once Curtis-Wright moved out of the region, hunting rights were restored, and the deer population was brought under control. Natural predators and parasites adapted to prey on the oak leaf roller. The forest has had a remarkable recovery since then; Now when Sidelinger drives down the Quehanna highway, the horizon is hidden behind a healthy forest. Even the white pine and hemlocks are stable for now! For one reason or another, certain stands of these trees weren’t harvested back in the day, and now those stands are protected natural areas. The white pine is even showing signs of a growing population as new germinating seeds are slowly spreading.

Later in his book, “Quehanna: A Blemished Jewel Restored,” Ralph Harrison wrote that, “the land is slowly recovering and, if man does not interfere and the climate does not change, perhaps in 500 years or so, the land may look somewhat similar to what it was 200 years ago.” However, when Harrison claimed to find a new plant every time he visited the Quehanna Wild Area, was he thinking about all of the species we have lost? Or is the diversity that sprung up from the devastation so great that he couldn’t help but marvel at it in spite of the region’s history? Is it necessary to long for a time before thoughtless colonists torched the earth of the Quehanna Wild Area, or is the resilience of nature itself the thing we admire? Whatever the case may be, this region is undeniably interesting, and if not for the Quehanna Trail drawing so much attention to it, the details of this story may have been lost to time.

Photo by Michael D. Reese, Moshannon Forest

History of the Quehanna Trail

Origin

The Quehanna Trail began with Ralph Seeley, an engineering professor from Penn State University who served as an advisor to the Penn State Outing Club (PSOC). People loved hiking in the Quehanna Wild Area, and Ralph spent his weekends dreaming of a loop trail in the region.

Parker Dam State Park was the perfect trailhead. It was the only state park in the area, and had all the amenities from parking to campgrounds. The trail would follow the existing paths from the Quehanna Wild Areas’ hunting, logging, and nuclear research days. To loop these trails together, Seeley recruited Ken Barnes, a forest fire specialist supervisor who used his connections with the BoF to get insider information on premiere trail locations from knowledgeable foresters. Seeley called Barnes, “The single most important person in bringing about the trails that you enjoy.”

Once designed, the relevant foresters and land managers all agreed to the installation of the trail. Construction began in 1976, with much of the work done by members of federally funded job programs. Since the trail was mostly laid on top of existing paths, the majority of “construction” was painting blazes. For new trail sections, paths had to be cleared of briars and laurels, bridges built over waterways, and sidehill trails dug into steep hillsides. To help with construction, Seeley mobilized volunteers from PSOC, and Barnes coordinated the foresters. By 1977, the Quehanna Trail was completed.

General Maintenance

Once built, trails require constant maintenance to remain open. Bridges will fail. Vegetation will take over in the sunlight. People will realize that there is an easier route to maintain, or more interesting destinations to see. In the beginning of the Quehanna Trail’s history, much of this work was done by YACC, PCC, and the BoF. Wade Dixon, for example, was the maintenance supervisor for the Quehanna Maintenance Division of the BoF, and did a significant amount of maintenance work. Seeley continued working on the Quehanna Trail by coordinating maintenance trips with PSOC, calling up Elk State Forest forester, John Sidelinger, to schedule these trips. Aside from the odd bridge failure or reroute, most of the Quehanna Trail requires little maintenance; mature trees shade the ground below, preventing briars and laurels from growing over the path.

Bridges

Bridges are an essential piece of trail infrastructure, and there are many along the Quehanna Trail. The Quehanna Trail crosses many trout streams, so many of its bridges use aluminum supports, which are thought to be unreactive with water. Much of this aluminum came from a government surplus, and Seeley writes that they “have been much appreciated.”

Many of the bridges along the Quehanna Trail were designed by Gert Aron, a retired professor of civil engineering at PSU. After a simple bridge of logs and planks began to rot over Red Run, Aron designed a bridge with an A-frame configuration of pressure-treated lumber. This design was used to replace many of the old bridges along the Quehanna Trail. Aron wasn’t the only bridge designed from PSU– Seeley designed a series of three footbridges over Mix Run. Those bridges were constructed by KTA and PCC. PSOC has also helped build some of the bridges along the Quehanna Trail.

Photo by @OneEyeWanderz, Quehanna Trail

Some crossings along the Quehanna Trail have proved more troublesome than others. Medix Run is infamous as the place “where footbridges go to die.” When the QT was originally constructed in 1977, a 135 foot bridge was installed over Medix Run. The untreated lumber began to rot, and was removed in 1991. Hikers had to cross through the stream for three years until KTA and RVOC volunteers installed a new bridge using Aron’s design. This was no small feat, taking over 550 volunteer hours, 90 paid hours, and $1840 (1994 prices) to build and install. Unfortunately, a flash flood in 1996 knocked out one of the support piers, twisting the bridge up like a pretzel. Remarkably, BoF and PCC were able to right the bridge, but erosion from the creek continued to wear away at the bridge’s supports. BoF installed reinforcements and diversion dams in 2001 and 2011, at which point the bridge was being held together by metaphorical duct tape. A flash flood destroyed the bridge for the last time in 2014. The Quehanna Trail was rerouted onto a former portion of the West Cross Connector Trail in 2016 to avoid crossing that point of Medix Run altogether.

Mosquito Creek is another infamous crossing of the Quehanna Trail. Recall that Corporation Dam created a deep layer of mud in this area, and that the streams carved channels into the earth. The rapid flow of the creek makes a wet crossing unsafe, but the deep, unstable mud of the former lakebed provides few locations stable enough to install bridges. This did little to dissuade hunters from crossing-construction. The first known bridge here was a “cable-supported/flimsy-decked” structure. So precarious was this bridge that many opted to crawl across. How relieved must hikers have been when Hurricane Ivan blew it away in 2004, allowing them to cross over a fallen birch log instead?

Three years later, QATC volunteers assembled a new 72 foot fiberglass bridge at the Deible Road ranger station. A woman from the PA Army National Guard carried it over to Mosquito Creek via helicopter. She lowered the bridge into place, while four foresters grappled with the dangling ropes to tie it down. The bridge cost $37,000, and an additional $5,000 were spent for preparation of abutments. This purported “permanent structure” was washed away in a flood just four years later. A piece of the bridge lies mockingly along the banks of Mosquito Creek to this day. In addition to the unstable terrain, installing a bridge at this crossing is difficult because in order for installation crews to get to the site, they’d have to cross Gifford Run, an exceptional value trout stream. An insurmountable amount of paperwork and permits must be fulfilled just to work at the site, not to mention the paperwork required for the actual bridge itself!

Reroutes

Reroutes have been done throughout the Quehanna Trail for just about every reason, from improving aesthetics to making the trail more practical to hike and maintain. The PA DCNR is responsible for many of the Quehanna Trail’s relocations, as they must approve any reroutes of the state forest hiking trail. KTA is often responsible for Quehanna Trail reroutes, as well.

There is one final reason that commonly necessitates rerouting a trail, and that when a disaster makes the current trail location completely inaccessible or dangerous. For example, the Quehanna Trail was rerouted in 2016 around a failed bridge at Medix Run, with the main trail assuming a former portion of the west cross connector trail. But that’s small potatoes compared to the reroute conducted in 1985.

Photo by Tasha Ferris, Parker Dam State Park

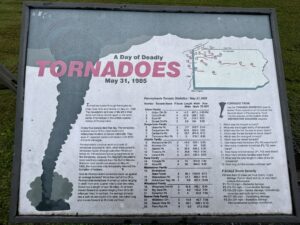

Tornadoland

On Memorial day of 1985, an F4 tornado touched down near Parker Dam State Park. Nearby, a boy scout troupe huddled in an old CCC camp. The wind beat against the building, sounding to the boys like a freight train. As the tornado passed by, it tore the roof from their shelter, leaving them scared, exposed, and luckily uninjured. The twister continued east, tearing the land asunder. The vegetation was shredded for 50 miles, the width of devastation ranging from 0.5 to 2 miles. There were no recorded fatalities in the state forests ravaged by the storm, but when the tornado touched down for the final time in Allentown, the people in a trailer park lost their lives.

The tornado destroyed every trail it came across, and the destruction in the Sauder’s Run valley forced the BoF to close the Quehanna Trail. Ideally the closure would be temporary, but without the means to repair the damage, the Quehanna Trail’s closure seemed indefinite. Tom Thwaites warned that, “If the trails are closed, nobody will hike on them. If nobody hikes on them, they will grow ever more closed with blowdowns and briars, and hiking will be even less likely. Soon we will lose all of those trails.”

Photo by Tasha Ferris, Parker Dam State Park

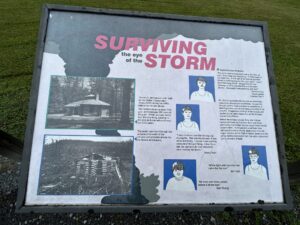

KTA had established a new trail maintenance program called Trail Care just three years prior, and reopening the Quehanna Trail was its first major project. Leading the initiative was the Trail Care chair, Dick Potteiger. Thwaites also took on a leadership role, rallying hikers to help restore their favorite trails across the state. Jean Aron was a passionate volunteer who documented much of the trail restoration in her memoir “Tornadoland.”

The first post-tornado trip to the Quehanna Trail was just trying to cut a path through the fallen trees. Since traditional tools like limb loppers and bow saws weren’t powerful enough to clean up after a tornado, volunteers offered their privately owned tools to assist with the project, and PSOC even loaned a chain saw to the initiative. Power tools increased productivity tenfold. People with chainsaws would generally forge a path, and the people behind would offer support, carrying gasoline for the chainsaws or tossing debris off to the side. Some volunteers, like Aron, worked as scouts, weaving their way through the wreckage to find the next trail blaze.

Ginny Musser joined the ranks of Trail Care on a later expedition to reopen the Quehanna Trail. After hiking out to the weekend’s work site, Musser was stunned by the destruction. “I remember standing on the trail, and no matter where I looked, all of the trees were downed… I had no idea how anyone thought they would ever, ever get the trail cleared.” Ignoring her doubts, Musser wielded a pair of loppers against the looming mountain laurels. At first she felt guilty because, “My word, that’s our state flower!” But to reopen the trail, it had to be cleared; forward she pressed. After a long day’s work, everyone gathered at the Weedville hotel for a Saturday evening dinner. They camped at Parker Dam State Park (for free, courtesy of DCNR) before doing another half-day’s work the following Sunday.

Photo by Tasha Ferris, Parker Dam State Park

In addition to KTA volunteers, the BoF assisted as well, helping to teach some of the volunteers safe operation and technique of power tools. In the end, much of the Quehanna Trail had to be rerouted on top of the plateau, following haul roads. This was the only way to get past the tornado zone.

The fifth and final Trail Care expedition to reopen the Quehanna Trail began the weekend of October 26. 24 people assembled at Parker Dam State Park, splitting into teams at both ends of the trail. Thwaites led the team headed north, and Potteiger led the south-going team. They met in the middle at the final obstacle– a massive blockade of three felled logs. The two men took a moment to shake hands across the barrier. Everyone got to work, and the Quehanna Trail was reopened that afternoon.

The Quehanna Trail was saved, but the work to keep a trail open never ends.The felled trees in the Saunders Run valley allowed too much sunlight in, allowing the briars to take over. Regular Trail Care maintenance trips were necessary to keep the briars back. Eventually, the blockades that necessitated the rerouting of the Quehanna Trail rotted down enough to be cleared away, and the forest recovered enough to shade out the briars on its own. KTA was able to put the Quehanna Trail back in the valley in 2001.

Maintainers of Note

Tom Thwaites, Ralph Seeley, and Ken Barnes

Although all three of these names have been brought up already, their work on the Quehanna Trail cannot be understated.

Tom Thwaites needs little introduction amongst Pennsylvanian hikers. “He was Mr. Trails,” claimed KTA volunteer, Ginny Musser. At one point, Thwaites was so famous that strangers in the woods would ask for his autograph if they crossed paths with him. It is unclear whether these particular hikers were in the woods searching for Tom Thwaites, or just coincidentally ran into him while on a hike. Thwaites’ fame was the culmination of countless volunteer hours of trail work with the KTA, establishing the Mid State Trail (another state forest hiking trail), and perhaps most importantly of all, his book “50 Trails in Central Pennsylvania.” These books inspired a new generation of hikers to take to the trees. Among those inspired is the author of “Guide to the Quehanna Trail,” Ben Cramer, who referred to Thwaites as, “Pennsylvania hiking authority.” Cramer credits Tom’s “50 Hikes” books with getting him interested in hiking in the first place, including his interest in the Quehanna Trail. Thwaites’ public outreach was remarkably effective at stimulating the public’s excitement about the outdoors, and the value of his work cannot be fully comprehended.

Tom Thwaites taught physics at PSU, and was one of the advisors to the PSOC. Perhaps this is where he became good friends with another hero of the Quehanna Trail, Ralph Seeley. Seeley’s name is suffused in this article, as he wrote extensively on the history, ecology, and value of the Quehanna Trail. It makes sense that the man who was the primary designer of the Quehanna Trail would write so much about it! Seeley also put in decades of work keeping the trail maintained, both volunteering his own time as well as coordinating maintenance events with the PSOC.

The final name of the big three maintainers of the Quehanna Trail is Ken Barnes, who throughout all of the research for this article was only referenced by two people. Seeley didn’t design the trail alone, and Barnes played an essential role in creating the trail. Seeley called Barnes, “The single most important person in bringing about the trails that you enjoy,” and given that Seeley was the primary designer of the Quehanna Trail, that praise has a lot of weight to it. Bob Merrill was the other person to mention Barnes, as the two of them had worked together at Moshannon State Forest. Merrill referred to Barnes as the go-to person for information on the Quehanna Trail during his time with the BoF. It is unclear why Barnes’ role with the Quehanna Trail has gone relatively undocumented, but the fact remains that the trail may very well have never existed without his dedicated efforts.

Photo by Miranda Van Bramer

Bureau of Forestry

Despite lacking the resources to maintain 100% of every trail in Pennsylvania, the Bureau of Forestry nevertheless found ways to provide invaluable support for these trails, including the Quehanna Trail. Authors Ben Cramer and Ralph Seeley both acknowledged the work of the BoF in their books on the Quehanna Trail. Aside from Ken Barnes, Bob Merrill and Ralph Harrison were both foresters that have been thanked by name across the literature.

Bob Merrill was a forester in the Moshannon State Forest charged with maintaining about four miles of the Quehanna Trail from three runs road to the Quehanna Highway from about 2011 to 2013. Merrill loves the Quehanna Trail, and has hiked, “parts of it several times.”

After Barnes, he was the go-to person for information on the Quehanna Trail. Seeley referenced Merril by name as a maintainer of the Quehanna Trail in his book.

Seeley also thanked a forest ranger from Elk State Forest, Ralph Harrison. Harrison spent nearly his entire life living in and around the Quehanna Wild Area, and became intimately acquainted with the region’s history. He eventually wrote a book on the subject, “Quehanna: The Blemished Jewel Restored,” but before that publication, there were few comprehensive records of the area’s past. Seeley consulted with Harrison in order to write his book on the region, “The Great Buffaloe Swamp.” Thanks to Harrison’s detailed accounts, the rich history of the Quehanna Wild Area is well documented by multiple sources.

Quehanna Area Trails Club

It is honestly baffling how this article has gone so long without mentioning the maintenance efforts of the Quehanna Area Trails Club. Perhaps it is because their work was so well done that there were no catastrophes of note to document. Still, this era of peace for the Quehanna Trail was only possible because of the countless hours of dozens of volunteers, and so QATC deserves a more thorough mention.

One day, Ralph Seeley suggested the idea of a trail club for the Quehanna Area to his friends, Edith (Edy) and Lee Hebel. The Hebels had a wide circle of friends and acquaintances, attracting 31 people to the first meeting on June 20, 1993, where the club was named “Quehanna Area Trails Club” to encompass both the Quehanna Trail and the Rock Run Trails that they sought to enjoy and maintain.

In the beginning, QATC offered one hike and one official work-day each year. However, that wasn’t enough for the Hebels, who continued to do much more maintenance on the QT on their own. Merrill once spoke with Edy Hebel after she “came in with a pair of hang clippers. She must’ve done half a mile of trail going through huckleberries and mountain laurel and all sorts of things to get that section of the trail that she was working on cleared.” Edy eventually became the sole club-coordinator, and before long, QATC was putting out newspaper notices and an annual newsletter as enthusiasm for the club and its activities continued to grow. At this point, hikes were a monthly occurrence from April through October. Around this time, the Hebels helped Seeley research some of the History of the Quehanna Wild Area for his book, “The Great Buffaloe Swamp.” Seeley gave the club the publishing rights for his books, the proceeds of which went right back to trail maintenance. Edy Hebel coordinated the hikes, work sessions, and paperwork for QATC for a decade before passing the torch to George Lockey.

Lockey was a painter, and worked on the trail with his time off. Merrill referred to him as “one of the major trail maintainers.” While he was QATC coordinator, Lockey spent countless hours out on the trail doing maintenance work. He wasn’t alone in this endeavor; Terry Desch accompanied him on many of these excursions, and was a “chief trail maintainer” of their own. During his time at QATC coordinator, Lockey made a website for the club that became the foundation of the next coordinator’s marketing strategy.

The final QATC coordinator was Rose Cheatle, and she ensured that the final years of the QATC would be documented and not forgotten. As time passed, many of the original club members were retiring and focusing their energy on other activities. Meanwhile, club recruitment had stagnated. Sometimes 25 people would show up for the monthly hike, and other times only one or two. Cheatle tried to reignite excitement for the Quehanna Trail by reworking the club website, but it wasn’t enough. On October 5, 2013, QATC had its last meeting after 20 years of service. The Quehanna Trail was placed into the care of KTA, until a new generation of passionate hikers band together for this trail once again.

For the 20 years that the QATC was in service, the Quehanna Trail was marvelously maintained. The club also helped promote the Quehanna Trail, so that in 1995 Thwaites wrote that, “this loop trail is only now beginning to attract the use it merits.” Even as the attendance to QATC events dwindled, Cheatle ensured that the legacy of the trail and the efforts of QATC would be preserved through KTA– much of the information in this section of the article came from an archived article on KTA written by Cheatle! The QATC truly did a wonderful job for this wild trail.

Keystone Trails Association (KTA) and volunteers gather for a Trail Care Weekend in August 2025. Photo by Al Germann.

Keystone Trails Association

Earlier it was established that the BoF lacked the necessary resources to maintain the state forest hiking trails alone, which is why volunteer work was so highly valued. A major source of volunteer labor for trail maintenance is the Keystone Trails Association. So far this article has covered how KTA helps conduct necessary reroutes, build bridges, and helped reopen the Quehanna Trail in 1985. Some specific volunteers of note are Dick Potteiger (first chair of Trail Care) and his wife, Lana Potteiger. They spent many weekends on the Quehanna Trail, helping to clean it up. When the QATC disbanded, KTA was able to fill in most of the gaps in trail maintenance.

Volunteers work along a trail during the KTA Trail Care weekend. Photo by Al Germann.

Many Others

There have been so many other groups that have served as maintainers of the Quehanna Trail, and it is impossible to mention them all. Even so, here are some of the other names of people/organizations that got the Quehanna Trail to where it is today.

The Ridge and Valley Outings Club has done all sorts of maintenance work, from clearing trails to building bridges.

In late 2007, boy scouts from the St Marys area built piers for a bridge across Trout Run.

A Boy Scout group called the Order of the Arrow relocated the Quehanna Trail to get it further away from the Marion Brooks Natural Area under the direction of scouting executive Terry Detsch.

Juveniles from Tressler Care Wilderness Service helped maintain a succession of switchbacks in November 2000.

PPFF Volunteers help set new bridges in state parks and forests.

The Quehanna Boot Camp has done a lot of regular maintenance on the Quehanna Trail. It is a minimum security prison that was established in 1992. Within the Quehanna Boot Camp are people convicted of non-violent crimes working through either a six month program modeled after a military boot camp or a 24 month program including counseling, treatment, and education. Both programs include community service, which often involves state forest maintenance and trail building. For example, they built a bridge over Beaver Run in 2008 after the previous one was destroyed by a hurricane.

The last person that needs to be mentioned is Betty Desch. The first mention of her in the research for this article was from Bob Merrill. “Betty kind of owns the whole trail,” he vaguely said. Desch isn’t associated with any organization. “She’s a lone wolf,” said Paul Shaw in an interview. She single handedly maintains dozens of miles of the Quehanna Trail, and has extremely high standards. She had thoughts on how Merrill was maintaining his assigned section of the trail with the BoF. “She wasn’t happy with the one section that I was working on so I figured, ‘Well Betty, you can take care of it, and fix it up how you want it,’” Merrill recounted. This wasn’t her only run-in with the BoF. She would remove certain signs or trail registers installed by the BoF, and would paint blazes along the trail to chase off horses (The Quehanna Trail is a state forest hiking trail, after all). Despite many disagreeing with her methods, Desch has become a kind of legend among maintainers of the Quehanna Trail. Shaw ran into Betty just once. He was climbing up a hill on the Quehanna Trail, when a woman sitting atop a log, looking out over the vista, came into view. “I just knew it was Betty,” Shaw declared. He asked her, “Are you Betty Detsch?” “Yeah,” she responded. Then according to Paul, “She took one look at me and said, ‘Where are your snake gaiters?’” Because Detsch isn’t affiliated with any organization, there is little to no written documentation of her efforts to maintain the Quehanna Trail. This is a shame, because her work is undeniably impressive. Shaw estimated that, “It would probably take 15-20 people to replace her.”

Photo by David Woodring, Moshannon State Forest

The Future of the Quehanna Trail

According to KTA volunteer, Ginny Musser, “Keeping a trail open is an ongoing project.” With that in mind, the story of the Quehanna Trail is far from over. Since QATC disbanded in 2013, the Quehanna Trail has been maintained mostly by the BoF, with urgent projects tackled by Trail Care volunteers. Other groups like boy scouts and the Quehanna Boot Camp likely continue to serve as trail maintainers as well. However, the only regular maintainer of the trail right now is Betty Desch, and it’s ridiculous that one person is able to keep the trail in such good shape by herself. Many other state forest hiking trails have dedicated trail clubs to keep them open, and it’s only a matter of time before the Quehanna Trail will need one again as well.

Until that happens, I urge you to recall the story of the Quehanna Trail the next time you walk outside. Think about where the path you’re following might have originated. Imagine how the landscapes you travel might have changed over time. Contemplate how many people worked hard to clear the ground you stroll upon. And finally, consider becoming a trail maintainer yourself.

In an article written for the Mid State Trail Association’s newsletter, “The Brushwacker,” Tom Thwaites made this assessment: “The total number of volunteer trail workers on ALL Pennsylvania trails, including the Appalachian Trail, is thought to be about 1,000, while the total number of hikers in the Keystone State is guesstimated to be about one million. So all the trail work is done by one tenth of one percent of the hiking community. The other 99.9% get a free ride, if you’ll excuse the expression.”

So many of the Quehanna Trail’s maintainers were normal people like you and me. Ralph Seeley and Tom Thwaites were professors. Lee Hebel was a pastor. George Lockey was a painter. Betty Desch drove a bus. All of these people found time to help maintain the outdoors that they loved so much, whether it be in the hours after work or over a weekend. They found purpose in their work, and often meaningful connections with others. Tom Thwaites once wrote that, “A few people with hand tools can work miracles… Physically and emotionally, the rewards of trail work are as real as they are little known.” When asked what she wanted people to know about Trail Care, Musser said that she just loves, “the camaraderie of working together, sitting on the trail and eating lunch together, camping together, eating dinner at the Weedville Inn on Saturday evening.”

I’ll conclude this call to action with a quote from Bob Merrill. In response to being asked what he wanted people to know about the Quehanna Trail and its history, he said, “there was a whole lot of heart and mind that went into the layout of that trail… Somebody’s interested in one particular area, so they go out and they’ll work on it. And then somebody else comes through and they say, ‘Well look what they did with this section!’ So they go and have another area that they’re interested in, and they’ll work on that section… A lot of that went on.”

Legend of Acronyms

QT- Quehanna Trail

PA- Pennsylvania

KTA- Keystone Trails Association

DoF- Department of Forestry

PSOC- Penn State Outing Club

BoF- Bureau of Forestry

YACC- Young Adult Conservation Corps

PCC- Pennsylvania Conservation Corps

PSU- Penn State University

RVOC- Ridge and Valley Outings Club

QATC- Quehanna Area Trails Club

DCNR- Department of Conservation and Natural Resources

CCC- Civilian Conservation Corps

Written by Eleanor Meckley, PPFF Summer Intern

Written by Eleanor Meckley, PPFF Summer Intern

Eleanor is pursuing her Bachelor of Science in Biology at Shippensburg University and is part of the school’s 4+1 program, which will allow her to complete both her undergraduate and master’s degrees in just five years. Eleanor’s passion for the outdoors shines through her love of field research, hiking, and fish—she especially enjoys sampling streams and exploring Pennsylvania’s waterways. Hiking to remote sites and scrambling over rocks are just a few of the ways she connects with nature throughout all four seasons.

Works Cited

Aron, Jean. “Tornadoland: Shaping the Growth of KTA Trail Care.” Keystone Trails Association, www.kta-hike.org/our-story-1976-1985.html.

Cheatle, Rose. “Remembering the Quehanna Area Trails Club.” Keystone Trails Association, archive-kta-hike.org/archive/post-870.html.

Cramer, Ben. Guide to the Quehanna Trail. Scott Adams Enterprises, 2015.

Hanes, Tom. 125+ Years of Recreation in the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry. Working paper.

Harrison, Ralph. Quehanna: The Blemished Jewel Restored. Pennsylvania Forestry Association, 2013.

“In Memoriam Tom Thwaites.” Hike the Mid State Trail, Mid State Trail Association, www.hike-mst.org/index.php/home/54-front-page/202-tom-thwaites.

Merrill, Robert. Personal interview with the author. 4 Aug. 2025.

Musser, Ginny. Telephone interview with the author. 14 Aug. 2025.

“Quehanna Trail.” KTA, www.kta-hike.org/quehanna-trail.html.

Seeley, Ralph. Foot Trails of the Moshannon and Southern Elk State Forests. 4th ed., Scott Adams Enterprises, 2014.

—. Great Buffaloe Swamp. 2nd ed., Quehanna Area Trails Club, 1995.

—. “My Favorite Trail.” KTA Newsletter, Aug. 2009, p. 1. KTA, www.kta-hike.org/uploads/8/2/5/0/82502470/aug09supplement.pdf.

Shaw, Paul. Personal interview with the author. 21 Aug. 2025.

Sidelinger, John. Telephone interview with the author. 21 Aug. 2025.

Thwaites, Tom. “A Brief History of Trail Care.” The Brushwacker, 2003, pp. 3-6.

—. 50 Hikes in Central Pennsylvania. 3rd ed., Backcountry Publications, 1995.