Bryan Wade, a veteran, historian, and most of all, an educator, sat down with us at the Pennsylvania Parks and Forest Foundation to share his insights on the intertwined histories of the abolitionist movement and the Susquehanna River. Having obtained his Bachelor’s of Science in Education from York College of Pennsylvania, Wade has been involved in various projects relating to the experience of African Americans throughout U.S. history, most of all, founding Keystones Oral Histories. Additionally, he has toured across the country to various universities to share his understanding of how racial constructs shaped and continue to shape American history. My interview with him shed light on seldom talked-about stories of freedom seekers and those who helped them across the mighty Susquehanna.

Brian K. Wade – Keystones Oral Histories

To begin this discussion, it’s important to highlight geographically why the Susquehanna held the potential to navigate freedom seekers. The Susquehanna River starts in Cooperstown, New York, and runs approximately 450 miles until it empties into the Chesapeake near Harve De Grace. This river meanders through 3 states acting as a signpost for many traveling north. This is important because not only did the river provide directions to freedom, but also food and water. Once the Underground Railroad began spreading in the North, the river became a beacon of hope. Bryan Wade helped articulate this story by highlighting the Susquehanna’s role in the Underground Railroad.

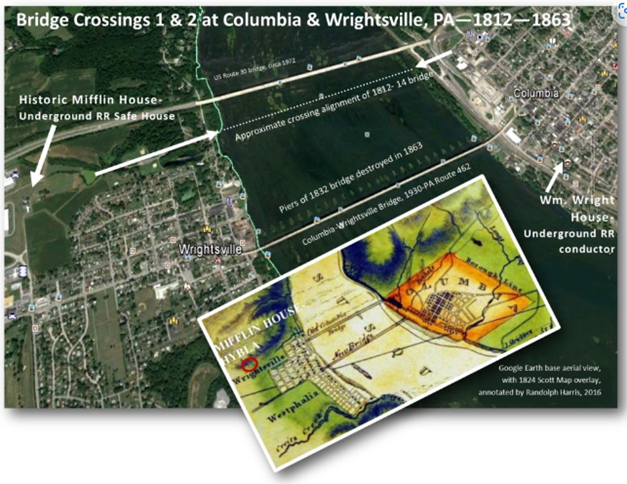

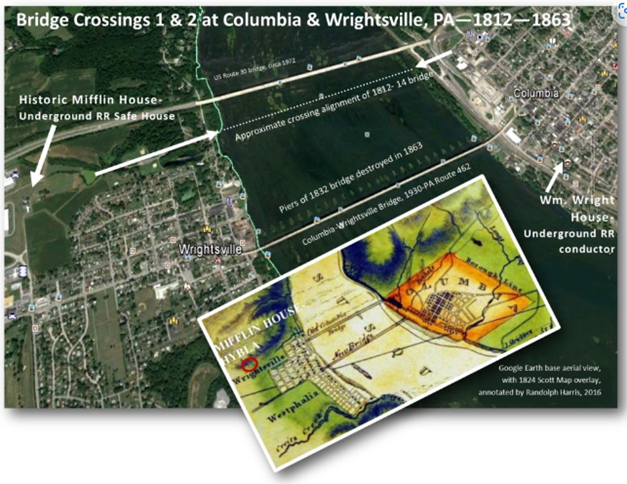

The river played a significant role in the fight for freedom by those fleeing oppression. Wade tells us that there were two major crossing points in the lower Susquehanna, Peach Bottom and Wrightsville.

Peach Bottom stands as a symbol of defiance against oppression, nestled near the Pennsylvania/Maryland border. Its location made it a natural stop for those fleeing from the south, seeking refuge and freedom across the Susquehanna River. The ferry at Peach Bottom played a pivotal role in facilitating this journey, serving as a lifeline for freedom seekers aided by conductors stationed out of Havre De Grace. With the help of the conductors, the freedom seekers risked their lives traveling north, through the terrain of southern York County, embodying the spirit of solidarity and resistance against the shackles of enslavement. Thus, Peach Bottom remains an enduring testament to the indomitable human spirit and the relentless pursuit of liberty amidst adversity.

Wrightsville’s significance stems from the Hybla House. Wade noted the relatively vast amount of historical documentation surrounding this location given the secrecy and lack of records that are typical for the Underground Railroad, making it notable for its rich history. The story begins with John Wright Sr., who established the ferry across from present-day Columbia, PA. Wright owned hundreds of acres of land, and after his passing, handed the land down to his children. But it was his grandchildren and great-grandchildren who were involved in the movement. During the Wright family’s tenure at the Hybla house, guided by their principles grounded in Quakerism, helped to quietly escort freedom seekers across the river. This went on for nearly fifty years.

This map shows the Underground Railroad locations in Columbia. This image is from the Lancaster History and Columbia Historic Preservation Society.

Both Peach Bottom and Wrightsville were influenced by the Quakers, most of whom lived in Philadelphia. But as these Quakers began to move westward towards Lancaster and Adams counties, they brought with them their ideals of equality and antislavery. This mix of geography, culture, and courage from those seeking freedom, made South Central PA a natural hub for those looking for a better future in the north.

It’s important to note that Wade highlighted that as much as the Quakers and abolitionist movement helped the freedom seekers in their path, it was truly the endurance and courageousness of the freedom seekers themselves. If it wasn’t for the thousands of individuals brave enough to seek freedom pioneering this path, it would have never developed. This is a necessary part of history to highlight that is often overlooked because of the lack of documentation. With the help of Wade, we can shed light on these stories.

The Susquehanna held significance because it provided the crossing points of the Pilgrim’s Pathway, a network of routes used by those going north. This quest was intercepted by the river, and while it was another challenge that needed to be overcome, it signaled their journey was not for nothing. This pilgrimage to freedom was plagued with constant trials and tribulations. Freedom seekers had to manage their survival in the face of hunger, fatigue, the elements of nature, and often, fear. Because of the Fugitive Slave Act, it was lawful for bounty hunters to pursue and capture freedom seekers brave enough to take liberty into their own hands. Making it to the Susquehanna did not guarantee one’s freedom, but the river represented a physical manifestation of hope, and hope for a better life in the north.

Apart from the Wright family’s long involvement in the railroad, Wade tells of another notable conductor named Samuel Berry. Berry was born an enslaved person in Maryland but bought his and his family’s freedom. They settled in York, PA, reaping the benefits of their newfound freedom. But this was not enough for the auspicious Berry. He soon found himself actively involved in helping others escape from their bondage. Berry shouldered a grave risk and arduous work by helping others. On at least one occasion he was beaten by bounty hunters because he gave refuge to a freedom seeker. Additionally, his daughter recounted that Berry would work all day, come home to rest for a few hours, and then in the cover of the night, tirelessly help others. Not only did Samuel Berry die a free man, but he died a man who dedicated himself to helping those who needed it most.

As for the communities around the Susquehanna, one can say that those who lived in them impacted the course of the Underground Railroad, but upon further inspection, we see that it was the Railroad that influenced the hearts of the people.

Wade tells us of the example of the Christiana Resistance. The year was 1851. The newly passed Fugitive Slave Act was still in its infancy and was soon to be tested. Freedom seekers who sought refuge in Christiana, PA, were pursued and confronted by Edmund Gorsuch, a slave owner from Maryland, who demanded possession of the escapees. However, the community refused, reasoning that Gorsuch’s rancid ideology had no place there. The encounter erupted into a gunfight in which at least 75 members of the town came to protect the escapees. In the end, the residents of Christiana protected the freedom seekers and Gorsuch was slain. This act of resistance against slavery and unjust laws is sometimes referred to as the first battle of the Civil War.

The federal government responded to the incident in Christiana by sending in Marines. The government arrested 37 individuals and charged them with treason. After a three-month trial and a successful defense mounted by PA’s own Thaddeus Stevens, the jury found the men not guilty. This verdict dispelled any illusions that the people of the lower Susquehanna area would not stand for injustice, which had a rippling effect throughout the North because it symbolized the first ideological victory of the Union prior to the war.

In closing, our conversation with Bryan Wade illuminated the intricate tapestry of anti-slavery history woven alongside the Susquehanna River. The history embedded in the river describes how the freedom seekers, with the help of the Abolitionist movement, fought and found their way to freedom. The Susquehanna’s history is long and varied, but its most crucial role is its part in the pathway north for freedom seekers. When standing on the riverbanks, remember the snapshots of history the river represents.

Written by Emily Myers

Emily is an AmeriCorps Member dedicated to environmental stewardship and community service. Currently serving at the Pennsylvania Parks and Forest Foundation and the Susquehanna River Trail Association as a Stewardship Coordinator Intern. She is committed to conservation and community improvement.

Sources:

- A Piece of the Underground Railroad’s Story Forever Told – The Conservation Fund

- Natural Mid-Atlantic : MD/PA: The Pilgrim’s Pathway, 30mi. (naturalmidatlantic.blogspot.com)

- RiverRoots: Underground Railroad at Hybla (susqnha.org)

- Smith, D. G. (2013). On the edge of freedom. [electronic resource] : the fugitive slave issue in south central Pennsylvania, 1820-1870 (1st ed.). Fordham University Press

- Switala, W. J. (2001). Underground railroad in Pennsylvania (1st ed.). Stackpole Books.

- The Underground Railroad in Columbia, Lancaster County – Pennsylvania Historic Preservation (pahistoricpreservation.com)

- Untitled-2 (susquehannariverlands.com)